Victorian women loved Shakespeare because he spoke the language of flowers

Some day, somewhere, if you happen to see Canterbury Bells growing in a field or perhaps an English garden, I hope you’ll think of me.

In Shakespeare’s era, people spoke the language of flowers and he used the language generously to add layers of depth and meaning that would move his audience.

It was the language of youth.

A secret language, spoken entirely in flowers and plants. The language of flowers was a way for young people to send each other messages that propriety would never allow them to say in words.

A young Victorian man would never tell an unmarried young lady that she stirs him to lust and physical desire. At least, not a proper young man. But he could say it in flowers, and that was entirely acceptable.

It’s part of why people were so moved by Shakespeare’s writing. The hidden meanings would grab the hearts of the young people who not only watched the play unfolding before them, but understood the hidden messages.

Today, those references escape us because we don’t know them, anymore.

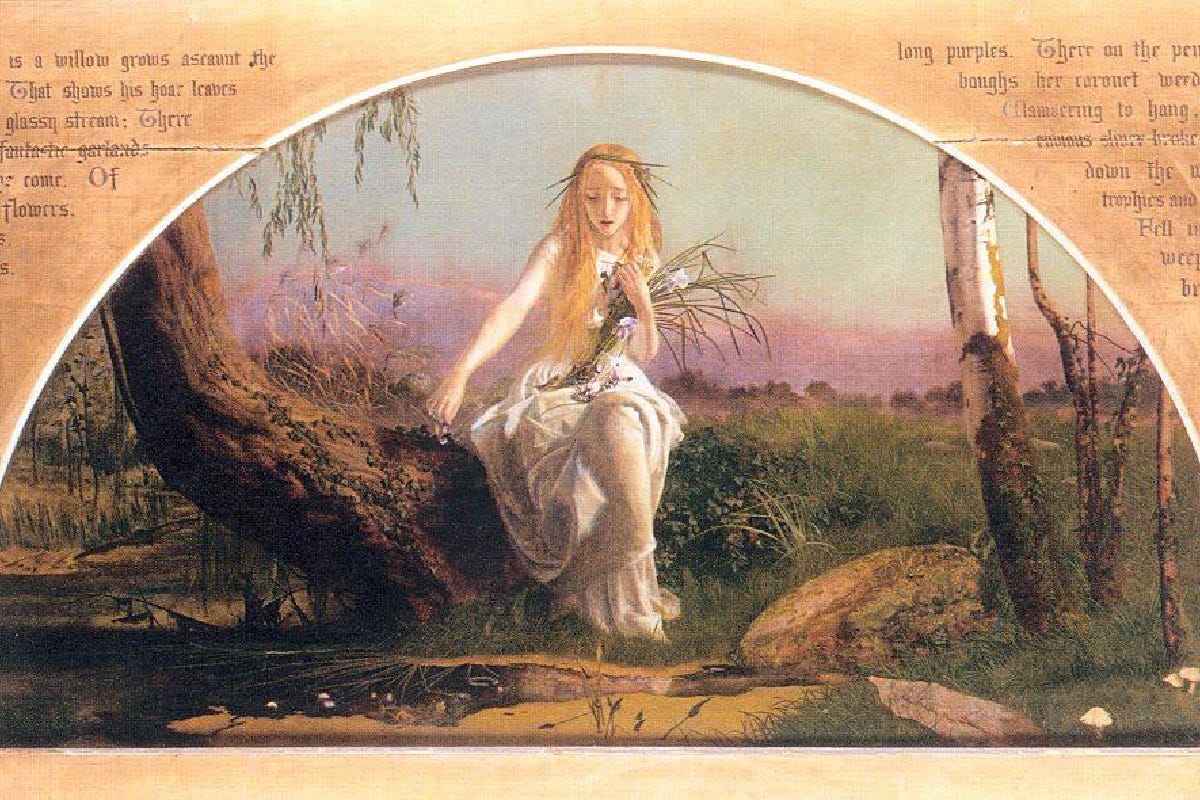

After Hamlet killed Ophelia’s father, poor Ophelia goes mad and at the end of the “mad” scene, she runs about handing out flowers.

…there’s rue for you; and here’s some for me: we may call it herb of grace o’ Sundays: O you must wear your rue with a difference. There’s a daisy: I would give you some violets, but they withered all when my father died…

She is speaking in the language of flowers and if you understood what she was really saying, it was achingly sad.

“Rue for you — and some for me” speaks of regret. Rue was an herb and it signified regret. She was filled with regret and remorse that she had such love and passion for the man who killed her father.

There’s a daisy — those three words alone spoke volumes. Daisies signified innocence. Hers. She was innocent. Didn’t see what was happening.

I would give you some violets, but they withered all when my father died — if her innocence and regret weren’t enough, the withered violets would have had the audience pulling out handkerchiefs to wipe tears.

Violets meant faithfulness and she’d love to offer some, but they all died when her father was murdered. She has no faith left.

She was innocent. Regretful. And now she is so broken.

It all started with a book from France…

As far back as Henry VIII, everything new started in France. The Boleyn sisters had been educated in France and came back wearing French fashion and clutching French books and became trend setters in stuffy old England. That was a few hundred years before the Victorian era, but the love of French culture never changed.

So, when a French book showed up it England, it was an instant hit.

A secret language for romance— from France? Done!

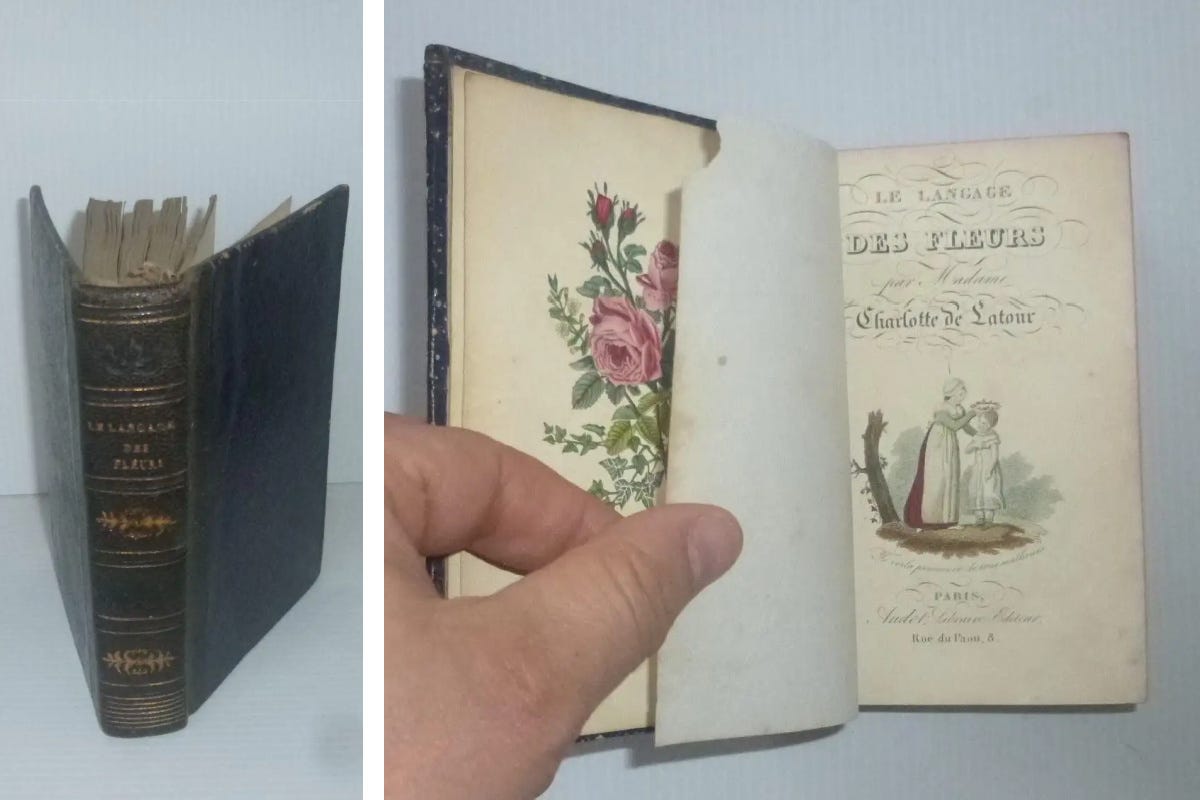

Le Langage des Fleurs (1819) by Charlotte de Latour was one of the first books about the language of flowers to sweep Victorian England, before crossing the pond to America.

It made perfect sense. Think English gardens — flowers and herbs were everywhere. Everyone had plenty at their disposal.

Young people loved that they could speak a secret language that their parents didn’t understand and didn’t care to. Parents watched fondly and indulgently as romance bloomed along with the blossoms. There would be grandchildren, indeed.

What do you do if a young man sends you a bouquet of red tulips?

That depends how you feel, darling, because it’s a confession of his love. A single yellow carnation is a firm no. Total rejection. Thanks, but no thanks.

And that’s that. He will no longer pursue you.

The flowers have spoken.

But maybe you want to let him down gently. Or stall a little. Then you’d send a striped carnation with oxalis, to express regret. Not rejection of him, but perhaps bad timing or other circumstance. That bouquet will hold him off but keep the door open in case the man you’re fond of doesn’t reciprocate.

Almost every household had that book sitting right next to the bible.

Young men and women alike would hurry to decipher the hidden messages every time flowers were delivered. It didn’t matter what message you wanted to send, there was a flower or herb to carry the message for you.

Many a young man enlisted help from a trusted sister or housekeeper to create the perfect bouquet. Florists did a booming business.

Lupins, hollyhocks, white heather and ragged robin to wish good luck.

Hydrangeas, oleander, basil and birdsfoot to tell someone they’ve been heartless and you’re disappointed and hurt.

A man could send a bouquet of nothing but yellow daffodils to express chivalry and unrequited love, hoping she would respond with love, or at least affection.

If he sends you gardenias with ivy? Fan those blushing cheeks, honey. And if there’s red roses with them? Well, just call the preacher and start planning the wedding.

Passion, lust, desire, anger, disappointment — it was all there. You only had to open the book and combine flowers and herbs to send a secret message.

It was beautiful, until it wasn’t.

As the language of flowers swept England and then America, more people hurried to publish books. They wanted to get in on a big thing.

By the early 1900s, there were more than 98 books about the Language of Flowers and that was just in America. There were even more in England.

If everyone had stuck to the same “meanings” and just created their own illustrations, it might have worked. But some authors decided to change the meanings of flowers and herbs because of their own personal preferences.

One book said buttercups are a promise of wealth and luxury, while another said buttercups mean the sender is calling you ungrateful and childish.

So which did he mean?

Offended by a bouquet, no one asked the sender which book they used. And slowly the language of flowers died away. Relegated to the history shelves along with Shakespeare and the meanings no one understands anymore.

Today, if you go to FTD, they’ll tell you roses mean love, and poppies mean remembrance. Daisies for innocence and heather for luck.

Only the basics remained.

A tiny handful of the most beloved flowers that no one dared change the meanings of. Who would deprive a bride her roses? But from time to time, the language of flowers still whispers of a romantic past among those who remember.

When Kate Middleton married the future King of England, she went out to the royal gardens and picked English Ivy and myrtle from a plant that Queen Victoria herself had planted way back in 1845 and gently tucked them in her bouquet.

She knew that in Queen Victorian’s day, ivy meant longevity and myrtle was the flower of lasting love and marriage. And she wanted those so dearly.

And with that, here’s my wish for you.

Some day, somewhere, if you see Canterbury Bells growing in a field or perhaps an English garden, I hope you’ll think of me. They mean eternal gratitude.

“The earth laughs in flowers.”

― Ralph Waldo Emerson

Fascinating as usual. What the victorians did with flowers, the youth of today manage with text messages, emojis, and memes.

"Almost every household had that book sitting right next to the bible."

I want one. I wonder if it's still in print?

I've known of the Language of Flowers but didn't know why the passion for it withered. All the different meanings.

Loved this article since I love flowers....and I loved learning about Canterbury Bells! Back at you, here's a bouquet